Udo’s response:

Hi Rick,

Actually, one could formulate an argument, like the contingency argument (see also here) that doesn’t simply assume that God exists when thinking about the question, ‘Why is there something rather than nothing?’ Rather, it is the argument’s conclusion that shows that God exists, or if you will, that it is more plausible than not that God exists given the nature of a contingent universe. As such the argument would constitute philosophical evidence for God’s existence.

So, instead of shying away from the question of ‘Why is there a God, rather than no god?’ such an argument confronts it head on. Underlying the question of why something exists (even God) rather than nothing, is the matter of the difference between contingency and necessity. Consider the question of why the laws of arithmetic are such that 1 + 1 = 2, or why the laws of logic is such that, for example, for any A it cannot be the case that both A and non-A are true at the same time and in the same sense. Why are these laws the way they are? Are they contingent, that is, could they have been otherwise (in other possible worlds) or are they the way they are by necessity (in all possible worlds).

So, if we ask why God exists, rather than not, we are asking about what it means to say that a being like God exists. Is God the kind of thing that exists by a necessity of its own nature, such as is plausibly the case with the laws of arithmetic or logic? Or is God dependent on other things for its existence, such as how humans or buildings or trees exists contingently? Some philosophers think it’s like asking if and how numbers exist. Well yes, the number 3 exists, they would say, by a necessity of its own nature – it cannot not exist. Similarly, the contingency argument aims to show that, given the contingent nature of physical reality, a being like God cannot not exist.

Now, the obvious problem with someone like Lawrence Krauss’ explanation that something like the universe came from nothing, is simply that the way in which he likes to use the word ‘nothing’, doesn’t mean ‘not anything’. It is scientific shorthand for the quantum vacuum state of energy, which clearly is something physical that can be described by the laws of quantum mechanics. So he is rightly criticized for using the term ‘nothing’ equivocally. More fundamentally it simply leaves the original question emphatically unanswered: why was there something, i.e. the quantum vacuum state, rather than nothing? There’s no reason to think that the quantum vacuum state existed necessarily rather than contingently.

Furthermore, how easily satisfied one is with particular answers, depends on many things. One difficulty is that people are often biased towards the ‘kind’ of answers that they would find satisfactory. For example, for some philosophers and scientists any reference to God is always and necessarily a non-answer, simply because all possible answers must and will refer to explanations and causes within the natural/physical realm (since, presumably, that is the only realm that exists). But the significance of this question of why something exists rather than nothing, is that it begs an explanation for why the natural/physical realm *itself* exists, specifically since every part of it seems to be contingent (in other words, it depends on something else for its existence or it is conceivable that it might simply not have existed in the first place).

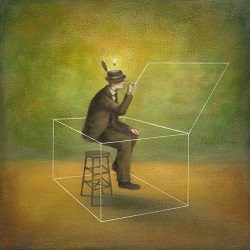

It seems there has to be something that is not contingent that would explain why anything and everything else exist. By definition that ‘something’ would not itself be contingent, and therefore would have to exist necessarily, in other words, by a necessity of its own nature. If everything is contingent, then no thing’s existence is ultimately explained, which is a very unsatisfactory idea indeed.

So, I’m glad that you recognize that the question, ‘Why is there something rather than nothing?’ is not a nonsense question (but it is interesting how some, notably atheist, philosophers and scientists do regard it as a nonsense question). I also have sympathy when somebody says that they don’t yet know what the answer is.

But my question is this: what kind of answer would satisfy? And more specifically, can we really not conceive of the kind of thing that would have to exist to explain the existence of everything else? For example, I’m not convinced that it’s merely a matter of being easily satisfied to think that the answer would plausibly refer to something that exists by a necessity of its own nature (i.e., it cannot itself be contingent) and therefore eternally, has intentionality/intelligence in order to choose to bring other things into existence (i.e., it cannot be a mere abstract object with no causal relations) and must be powerful enough to bring other things into existence. What is interesting is that these minimal properties that such a thing would need to have, corresponds quite well with what is usually meant when referring to the concept of ‘God’.

So, would such a God ever ask himself where he came from? Probably not, and for two reasons: 1) If God is all-knowing, as traditionally understood, then the question would simply not come up, and 2) if a necessary being exists, then there simply is no more basic or fundamental answer than that it is part of the nature of that thing that it exists necessarily (i.e. any other conceivable answer would suggest contingency and therefore it wouldn’t exist necessarily).

Leave a Reply