The following is my response to one of three articles written by Jonathan Garner on the issue of properly basic beliefs and whether we need evidence or arguments before we are rationally justified to believe in God.

_________________________

I quote (in bold) from Garner’s article and then comment as follows (read the full article here: https://jonathandavidgarner.wordpress.com/2017/11/10/the-superfluousness-of-reformed-epistemology-and-other-problems)

You write:

“One problem I have with this is that I think reformed epistemology (or anything similar) is superfluous. In other words, I think it is unnecessary. Why is that? Well, most theists (and even a lot of atheists, if not most atheists) think that the arguments for God’s existence provide prima facie support/justification for belief in God’s existence. Sure, the arguments might not be very compelling to a lot of nonbelievers, but the issue here is not epistemic obligation; rather, the issue is epistemic permissibility.”

There might well be sufficient evidence (prima facie or not) for God (as I think there is), but how does this fact make believing in God without evidence superfluous? If anything, it is precisely the other way around. It is when we can have a non-inferential immediate knowledge of God, that makes evidence for belief in God unnecessary and therefore superfluous. This being said, I don’t think that coming to know God non-inferentially excludes the importance or value of showing that God exists according to the available evidence. It’s not a matter of either/or, but of both/and.

You write:

“If a Christian can’t say that, I question whether they really are rational in their belief that God exists. That’s because you’d essentially be saying that you have no idea whether reality should look the way it does if God exists. In that case, you should suspend judgment about whether God exists. Or worse, you think the world looks like it would if God does not exist, yet you continue to believe that God exists!… The fact is that we at least have some general idea what the world would like if there were a God. For instance, we would expect there not to be a universe where there is non-stop suffering or torture from beginning to end. Luckily, we don’t live in a world where there is only pain. If there was only pain, that would be evidence of an evil god!”

There are many people who apparently find themselves in a position where they can’t determine, based on the evidence alone, on whether reality is what you would expect if God exists. This is partly the reason why Pascal introduces his wager and says that it would be rational for such people, not to suspend judgment, but to choose for pragmatic reasons to live as if God exists and that true belief will eventually follow.

Also, I’m not sure what the point is about a universe with non-stop suffering. Yes, you wouldn’t expect such a universe if God exists, but that is irrelevant. There is enough prima facie evidence of evil and suffering in the real world, so many non-theists argue, to keep them from believing that this is the kind of world that you’d expect God would create. Now, I think there is an answer to this, but the point is that even the theist could be so immersed in pain and suffering, that they too wouldn’t in good conscious say that the world looks like a place that they’d expect if God exists – but who nevertheless found themselves with the belief that God is real. It is no stretch to think there were many theists like this throughout history, who were for most of their lives under severe persecution or suffering, in circumstances of prolonged pain or continuous oppression, restricted to small geographical or cultural areas, and cut off from the wider world, and who still believed in God. According to your line of thinking here, these believers were all decidedly irrational in their belief. In this scenario, belief is something you can only justifiably have if you are lucky enough to live in a time and place where you could experience enough prosperity and happiness so as to reasonably infer that God, a good God, probably exists. But now, since some believers have experience mostly misery on a daily basis, you are banished to epistemic darkness from which you cannot escape even if God is real.

I wonder if Job would have agreed with this assessment.

You write:

“But, my main problem with reformed epistemology is that it would justify all sorts of beliefs, including beliefs that many Christians wouldn’t want to say have epistemic justification like belief in Islam. One might try to lessen the blow here by suggesting that Muslims only have prima facie justification for their belief in God based on religious experience (just like the Christian). Even if this is true, it would have the further implication that convincing someone from another religion is going to be difficult. Not to mention, reformed epistemology would seem to justify crazy beliefs like belief in voodoo. This means that something is wrong with reformed epistemology….even if we don’t know exactly what it is.”

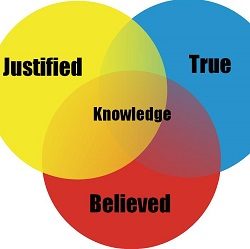

This is simply a misunderstanding of what reformed epistemology claims. If you’re familiar with epistemology in general you would know that epistemic justification is relatively easy to have (yes, a belief in voodoo probably not excluded), and not at all peculiar to reformed epistemology. Someone might be justified in having a certain belief given their circumstances and background knowledge, even if such a belief turns out to be false. Clearly such a false belief, though justified, would not be warranted since it’s not true and therefore cannot be considered knowledge. So the issue that reformed epistemology is concerned with is one of warrant, in particular that belief in God is warranted if and only if theism is true. This means that even if someone claims a particular belief is basic to them and even if they have prima facie justification (like the Voodooist or Muslim), then it might still not be properly basic (in the sense of having warrant) if it can be shown to be false. The fact that it might be difficult to show that someone’s prima facie evidence does not warrant their beliefs, is neither here nor there. Weighing evidence and arguing soundly mostly is simply a difficult endeavor. But the point is that reformed epistemology does not imply that any old belief is warranted.

You write:

“Another problem I see is the problem of conflicting religious experiences….”

I don’t see what the problem with conflicting religious experiences is supposed to be. You certainly don’t have to accept reformed epistemology to realize that when people claim all kinds of different religious experiences that not all such experiences can be veridical, especially if only the Christian God exists. But at the same time you don’t have to feel the need to defeat every seemingly conflicting religious experience since many of those experiences might well be veridical simply because God is truly involved in many experiences people might have, even if they don’t initially recognize God for who he truly is.

You write:

“Fundamentally, one shouldn’t be asking whether their belief can be rational or reasonable. Rather, a person should be more focused on whether their belief is actually true. One might find themselves with a particular belief, and one might find the belief to be reasonable at face value. On the other hand, one is still under an epistemic obligation to find out whether that belief is actually true. If one isn’t required to “error check”, then one can justify all sorts of things based on their seemings. For example, one can say it just seems like Obama isn’t a U.S. Citizen, or a jury member can say it just seems like the defendant is guilty. Even if one is prima facie justified in believing these things, that does not entail they aren’t obligated to seek out independent evidence for their respective beliefs.”

Of course one should be concerned about whether your beliefs are true. The point of reformed epistemology is just that when you find yourself with a particular belief, then you don’t assume that it’s not rational, justified or warranted to hold that belief simply because you can’t give reasons for its truth. Some beliefs are properly basic, in other words, they are the kinds of beliefs produced, not by inference, but simply by your cognitive faculties when they are functioning properly in the right kind of cognitive environment. Thus, if you find yourself with the belief that you had eggs for breakfast, then you don’t have to provide yourself with evidence for such a belief in order to know that you had eggs for breakfast. That you know, in such a case, is not dependent on any evidence that would explain why you know it.

Are you therefore under an epistemic obligation to find out whether the belief that you had eggs for breakfast is true? No, not if such a belief is properly basic – this is the insight of reformed epistemology. It doesn’t mean that the truth of a belief can’t be challenge, even if it seems properly basic. There could well be reasons that make it apparent that a particular belief is not properly basic after all. To knowingly ignore such reasons is unquestionably irrational. But until and unless such reasons are evident you are not obviously or necessarily irrational, unjustified or unwarranted in holding a specific belief without evidence.

When someone therefore says that something just seems to them to be the case, then they might hold such a belief in a basic way, but it doesn’t make it properly basic, especially not if there are reasons to think it is false.

You write:

“In fact, one might even come across good evidence that one’s belief is false. Someone might object that a person’s religious belief is like the person who believes they are innocent when all the evidence shows that they are guilty. But, this analogy is somewhat misleading. One can think of an analogy where one initially thinks they are innocent, but they are shown very good evidence that they are guilty. It might be further objected that belief in God’s existence is non-inferentially justified, so it doesn’t matter what the total evidence indicates about God’s existence. This is false. Just because a belief is not based on another belief, doesn’t mean that the belief can’t be defeated by evidence. That would be like saying my belief that there is clown or monster outside my window can’t be defeated because it is basic/non-inferential belief. If the total evidence indicates that God doesn’t exist, I should not dig in my heels and appeal to my seeming. Rather, I should say that my seeming ended up being wrong. After all, seemings are not even close to being infallible.”

The possibility of defeaters is both recognized and important in RE because it shows that if there is evidence that theism is false, then a belief in God is not warranted (apart from the presence of any intrinsic defeater-defeaters, which we come to shortly) even if it justified and rational. So RE is indeed concerned with the truth of theism, it just says that to know theism is true is not dependent on any evidence, if theism is indeed ontologically true.

You seem to misunderstand the purpose of the analogy as it is often used with regards to reformed epistemology. The analogy speaks to the nature of some properly basic beliefs, where some beliefs are so overwhelmingly warranted that they serve as intrinsic defeater-defeaters. Thus, if a person knows they haven’t committed a crime, then their belief in their own innocence is not only properly basic if indeed they didn’t commit the crime, but serves as an intrinsic defeater-defeater. This means that even if all the evidence (serving as possible defeaters) would somehow show that they are guilty, then they are under no rational obligation whatsoever to accept that they did commit the crime after all. Not only should they not accept this, but it would be irrational to do so for their knowledge of innocence serve as an intrinsic defeater of any defeaters that may be given. It doesn’t help to suggest that some good evidence might convince someone to the contrary, because that merely assumes that such a person somehow didn’t really know they were innocent. But this is precisely what the analogy denies: they can and do know that they are innocent, even if all the evidence somehow point to their guilt, and therefore shouldn’t accept any guilt.

___________________________

[Garner quotes from my response and replies as follows:]

“There might well be sufficient evidence (prima facie or not) for God (as I think there is), but how does this fact make believing in God without evidence superfluous? If anything, it is precisely the other way around. It is when we can have a non-inferential immediate knowledge of God, that makes evidence for belief in God unnecessary and therefore superfluous. This being said, I don’t think that coming to know God non-inferentially excludes the importance or value of showing that God exists according to the available evidence. It’s not a matter of either/or, but of both/and.”

How would it work the other way around? The arguments would still be used for nonbelievers.

“According to your line of thinking here, these believers were all decidedly irrational in their belief. In this scenario, belief is something you can only justifiably have if you are lucky enough to live in a time and place where you could experience enough prosperity and happiness so as to reasonably infer that God, a good God, probably exists. But now, since some believers have experience mostly misery on a daily basis, you are banished to epistemic darkness from which you cannot escape even if God is real.”

This is only a problem if you assume that God would make the world exactly like what we see. I think you see where I’m going.

“This is simply a misunderstanding of what reformed epistemology claims. If you’re familiar with epistemology in general you would know that epistemic justification is relatively easy to have (yes, a belief in voodoo probably not excluded), and not at all peculiar to reformed epistemology. Someone might be justified in having a certain belief given their circumstances and background knowledge, even if such a belief turns out to be false. Clearly such a false belief, though justified, would not be warranted since it’s not true and therefore cannot be considered knowledge.”

No, that’s Plantinga. And Plantinga’s views have changed over the years, and Plantinga is not synonymous with reformed epistemology. Plantinga, personally, now thinks epistemic justification is easy to come by.

“The possibility of defeaters is both recognized and important in RE because it shows that if there is evidence that theism is false, then a belief in God is not warranted (apart from the presence of any intrinsic defeater-defeaters, which we come to shortly) even if it justified and rational”

That’s totally wrong. There is evidence for all sorts of claims we know are false.

“You seem to misunderstand the purpose of the analogy as it is often used with regards to reformed epistemology. The analogy speaks to the nature of some properly basic beliefs”

Stop saying I am misunderstanding. I don’t buy the analogy because I don’t buy the conclusion. Do you even know what analogies are and what they do? What they can do?

______________________________

[Garner responds again, and I reply:]

“How would it work the other way around? The arguments would still be used for nonbelievers.”

I don’t understand your question since I HAVE explained how it would work: “It is when we [i.e., believer and nonbeliever] can have non-inferential immediate knowledge of God,that makes evidence for belief in God unnecessary and therefore superfluous.”

“This is only a problem if you assume that God would make the world exactly like what we see. I think you see where I’m going.”

No, I don’t see where you are going. It is in this particular world that I find myself with a belief that God exists. So, if God does indeed exist in this world (according to Plantinga’s model), and my belief is therefore warranted, why on earth would I think that this isn’t the world that He created?

“No, that’s Plantinga. And Plantinga’s views have changed over the years, and Plantinga is not synonymous with reformed epistemology. Plantinga, personally, now thinks epistemic justification is easy to come by.”

I suspect that very few reformed epistemologists, if any, would answer in a substantially different way than Plantinga to the objection that simply any kind of belief is justified on their view. And even where Plantinga does not speak for all RE’s, it doesn’t mean he is wrong.

“That’s totally wrong. There is evidence for all sorts of claims we know are false.”

Why is that totally wrong? In fact, I agree fully with your statement that “there is evidence for all sorts of claims we know are false” (that is precisely why Plantinga says justification is easy to have). But how does this contradict the fact that if there is evidence that show a claim to be false, then believing such a claim is probably not warranted?

“Stop saying I am misunderstanding. I don’t buy the analogy because I don’t buy the conclusion. Do you even know what analogies are and what they do? What they can do?”

I’ve touched a nerve! Sorry! Please note that I haven’t merely said that you are misunderstanding, I have made an effort of trying to explain WHY I thought so. So, instead of merely casting suspicion on the sufficiency of my knowledge, you might consider returning the favor. Isn’t that the more responsible and reasonable thing to do?

Leave a Reply