- Eusebius McKaiser’s pre-discussion comments: No need to treat God with kid gloves (here is the talk-show interview with John Lennox that Eusebius refers to)

- Eusebius McKaiser’s post-discussion comments: Why God’s not a moral imperative

- Winston Mashua, moderator of the discussion, comments: Pondering issue of God and morality

- John Lennox comments as follows:

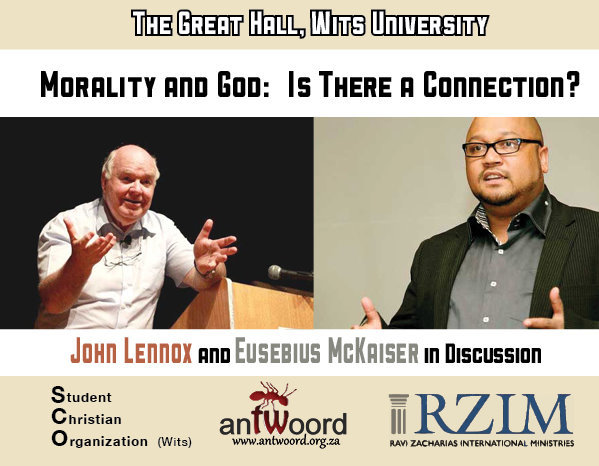

I enjoyed the discussion with Eusebius McKaiser in the Wits Great Hall last week, ably moderated by Winston Mashua, and I am sure that your sense of fairness will allow me to respond to the two articles that have appeared under McKaiser’s name commenting on the Wits discussion.

The second article starts, rather oddly, with a matter we did not discuss at all – Plato’s famous Euthyphro problem: “is murder wrong because God says so, or is it wrong regardless of what God thinks”. Notwithstanding Eusebius assertion that Christians find this difficult, such is not the case. His mistake is to think that if things are right or wrong only when God gives his view, then morality becomes arbitrary. This is to separate God’s will from his character. God is good by nature and so what he commands is good.

His first article got off to rather a bad start for a philosopher. He wrote: “Being agnostic I obviously think he’s wrong.” Well, an agnostic is someone who doesn’t know, so what ought to be obvious is that agnostic McKaiser doesn’t know whether I am right or wrong. The mind boggles.

McKaiser then went on to allege that John Matham had given me “a good grilling” on Capetalk and that “several listeners were upset”. However, I had no sense that Matham had grilled me – we had a vigorous discussion and, in any case, grilled meat is better than raw! I was not aware of any upset listeners – unless they were atheists disturbed at my arguments.

McKaiser’s main discussion thesis was that moral reasoning has rational justification without reference to God. That is, there is a “natural law” that we perceive with our rationality. There are moral facts that “we cannot not know”, to cite natural law philosopher Jay Budziszewski. Indeed, the Bible itself refers to people whose attitude to their families shows that they lack “natural” affection. So Eusebius professed shock at my citing the well-known natural law tradition positively is rather revealing. I was not conceding anything but simply saying that his argument had some merit.

The reason for that, from the Biblical perspective, is clear. Human beings are made in the image of God so that they are not only rational but moral beings. That moral dimension to their rationality as created by God accounts for a common pool of moral conviction that is discernible across humanity of all beliefs and none. For McKaiser to say that he can put “Christian ethics on the back foot in 800 words” seems absurd since his main argument is a worthy part (but only part) of Christian Ethics in the first place.

For, as I said in the discussion, there is more to this matter. David Hume pointed out long ago that it was impossible to get “ought” from “is”. McKaiser conceded that this was a problem and he “needed to do more work on it”. I think he may.

The biblical view that humans are created as moral beings makes far more sense. The explicit verbal revelation of God’s moral standards at Sinai confirms what our conscience tells us. Murder did not first become wrong at the moment the Ten Commandments were uttered.

In spite of several attempts I failed to get McKaiser to see the central problem. He places all of his faith (yes, faith) in his rationality. But the key question is that without God he would not exist let alone have his rationality. He writes: “where rationality comes from is a question for another day”. But it isn’t. His whole argument depends on the reliability of the human mind and if we deny the existence of God then that reliability vanishes.

American philosopher Alvin Plantinga cites Richard Dawkins – a person, incidentally but interestingly, that McKaiser treats in his first article with more kid-gloves than he does God. Plantinga writes: “If Dawkins is right that we are the product of mindless unguided natural processes, then he has given us strong reason to doubt the reliability of human cognitive faculties and therefore inevitably to doubt the validity of any belief that they produce – including Dawkins’ own science and his atheism. His biology and his belief in naturalism would therefore appear to be at war with each other in a conflict that has nothing at all to do with God.”

Similarly, avowed atheist philosopher Thomas Nagel writes: “Evolutionary naturalism implies that we shouldn’t take any of our convictions seriously, including the scientific world picture on which evolutionary naturalism itself depends”.

McKaiser, as a moral philosopher, needs a valid rationality to take his convictions seriously just as I do as a scientist and it was very clear in the discussion that he was unable or unwilling to respond to the arguments I made from a scientific perspective. That was his prerogative, of course, but then to assert that he did not accept my arguments because they did not reach the standards of good argument in rational discourse, appeared very weak. An assertion is not an argument – and he gave no argument that I could see on this score. Indeed, in jettisoning God, McKaiser gives me every reason not to take any of his arguments seriously.

In the current debate about science and God the status of human reason plays an increasingly central role and very few would think that the “McKaiser argument” settles the matter – “if I can do science without mentioning God then I don’t need God”. Ironically, as I pointed out at Wits, it was belief in God that drove the rise of modern science in the first place.

Since reason cannot be grounded without God then McKaiser’s case for reason-based morality also fails. He cannot evade this question by saying that my argument amounted to claiming that: “just because my mum gave birth to me, she is a necessary part of the explanation of how I solve a maths problem”.

For, she is in fact a necessary part of the ultimate explanation of how he has the ability to solve a maths problem in the first place. McKaiser might even have inherited his mother’s mathematical ability, which explains in part why he is good at maths.

McKaiser is a rational person because his origin was rational and personal. And we all are rational persons because our origin is not in a mindless unguided naturalistic process, but in the creative power of God.

McKaiser ends by saying to God: “If you disappeared tomorrow, I’d still know the difference between right and wrong”. Sadly, he would not. If God disappeared tomorrow so would Eusebius McKaiser, together with the whole cosmos.

It won’t happen. Ironically, McKaiser’s existence and his capacity for moral reasoning are part of the evidence that God, the rational and eternal Creator, is very much alive. On the other hand, by failing to ground rationality, the atheist philosophy of naturalism does not simply shoot itself in the foot – that is painful enough. It shoots itself in the brain. And that is fatal.

Finally, I agree wholeheartedly with McKaiser that we need more open, critical, vigorous yet friendly discussion on such matters and I trust that our conversation at Wits demonstrated that this is eminently possible.

John Lennox

Professor of Mathematics

Oxford University

A few other interesting comments:

Leave a Reply