By Rudi De Beer

Introduction

It has been said that life is like a game of cards, the hand dealt is determinism and the hand played is free will. The problem with this simplistic view is that God’s divine omnipotence is limited and subject to the freedom that humans can exercise. On the other hand, if God determines all things human free will is diminished. Traditionally this has led to the troubling idea that divine providence and human free will cannot both be true at the same time.

This apparent contradiction can be defused by means of biblical, theological, and philosophical arguments.[1]In this paper I will illustrate with the concept of “middle knowledge” that absolute free will and complete divine determinism does not have to be mutually exclusive.

In order to do this, I will firstly explain some basic concepts of divine knowledge. I will then present the case for Molinism and argue that it provides adequate explanatory power to support my thesis.

Divine knowledge

More or less all Christian theologians believe that before God decree a specific world to exist, He possesses complete knowledge of all possible worlds that could exist. Among these possible worlds could be a world in which Peter denies Christ three times as well as a world where Peter affirms Christ in precisely the same circumstances. This concept known as Natural knowledge gives God knowledge of all that could be, irrespective of what he would finally decree.[2]

Furthermore, if one would argue that human beings are able to exercise free will in all of these possible worlds, there could be an unlimited amount of scenarios. A typical hypothetical scenario is defined by a condition or premise followed by a consequence in the form of a counterfactual statement. For example, “If I were a Millionaire, I would buy a Ferrari” or “If I share the gospel with my neighbour, he would accept Jesus as his saviour”. This concept of knowing the specific outcome, given a specific condition, is known as Hypothetical knowledge and gives God knowledge of all that would be, based on all possible human choices.[3]

Finally there is strong consensus among Christian theologians that once God has decided that a specific world will exist He possesses complete knowledge of all past, present and future knowledge of this world. For example long before our actual existence God knew that terrorists would fly into the World Trade Centre on September 11, 2001 and He also knows the exact time and day that the 100th president of South-Africa will be born. Theologians refer to this as Free knowledge and it gives God knowledge of all that will be.

Molinism

Inspired by Luis de Molina, Molinism argue that God accomplishes His perfect will while at the same time ensures complete human freedom to choose. This is achieved when the three concepts of divine knowledge listed above is arranged in a specific logical order: 1) Natural knowledge, 2) Hypothetical (or Middle) knowledge and 3) Free knowledge.[4]However, it is important to note that these concepts do not occur sequentially in time, but are only logically arranged. In other words, all three concepts of knowledge occur at the exact same time prior to God’s divine creation decree.

Consider this: There is one possible world with a specific set of circumstances without any humans. Everything in this world can be determined without violating any free will since there are none. This world is completely deterministic hence there can only be one specific possible outcome of this world and it achieves exactly what God wants to achieve.

Now, a human being (with free will) is placed inside this possible world without changing any conditions of this world. By the characteristics of complete free will there can now be a multitude of possible worlds with the exact same circumstances and conditions. The only differences between these possible worlds are the set of different choices made by the human. In all other respects they would be identical.

At this logical point, these worlds don’t exist yet and also God possesses no other knowledge about these worlds except that they all could exist. He is not aware of what the human would choose in any of these worlds. God therefore knows everything that could be, but not that would be or will be. Should God at this logical point choose to actuate any of these worlds it is irrelevant of what the human would choose or even that the human had a choice at all, since it is subsequent to and determined by His divine decree.

In fact, there would be no difference between this chosen world and the initial scenario mentioned where the human were not present in the world. This world is completely deterministic without any “feedback” from what the human would have chosen in any of these worlds. In other words, God chooses a world that He desires without considering human free will at all. The result is a world where human freedom is apparent only and not real.

To resolve this problem, Molinists propose that in the logical moment following God’s Natural knowledge but prior to His divine creation decree, He possesses Hypothetical Knowledge. Since this knowledge is in the middle between Natural knowledge and Free knowledge, Molinists are referring to it as Middle knowledge.[5]

Molinists argue that without this Middle knowledge the only way that God could be certain of a specific outcome in a specific world would be to force the choice of the human. However, if God had all the information beforehand (knowledge of what could be as well as what would be) He can choose from all these possible worlds the specific worlds that are feasible to Him. These worlds would accomplish what He wanted to happen while still allowing the human complete freedom to choose.

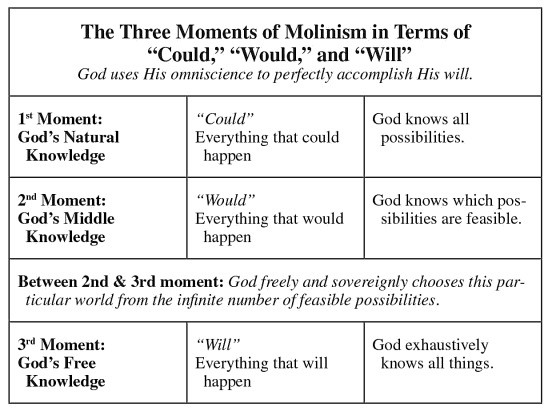

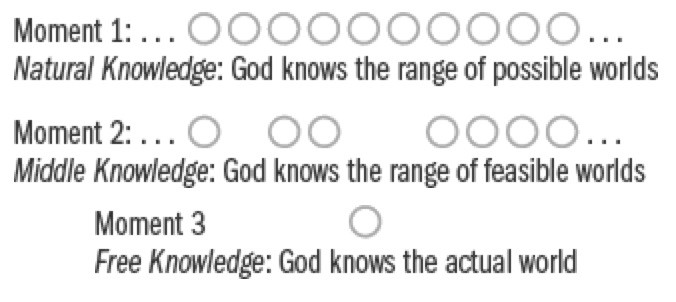

Once God has created a short list of these feasible worlds He is able to choose an actual world He wishes. Knowledge of this world that He will choose is what Molinist are referring to as Free Knowledge. This would be the third logical moment of knowledge before God’s divine creation decree. These three moments can be summed up in the following diagrams from Kenneth Keathley and William Lane Craig respectively.

Figure 1.Molinist moments of knowledge. Sources: Kenneth Keathley, Salvation and Sovereignty: A Molinist Approach (Nashville: B&H Publishing Group, 2010), 17.

Figure 2.Molinist moments of knowledge.Sources: Dennis Jowers, William Lane Craig, Ron Highfield, Gregory Boyd, and Paul K. Helseth, Four views on Divine Providence (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2011), Kindle Location 1582.

Craig argues that even though it is difficult to prove that God has Middle knowledge, it is clear from scripture that He has Hypothetical knowledge.[6] For example, Jesus affirms before Pilate “If my kingship were of this world, my servants would fight, that I might not be handed over to the Jews” (John 18:36 RSV). The question remains however in which logical order God possesses this knowledge. Since it is unclear from the Bible where this Hypothetical knowledge logically resides, Craig argues, we have to turn to theologico-philosophical reflection to safely infer this from scripture.[7]

From a purely theological point of view, Molinism has a great deal of explanatory power. For example divine foreknowledge and divine providence follows automatically out of the logical order of the Molinistic concepts of knowledge. For example it is clear that Jesus’ crucifixion was predestined by God while at the same time orchestrated by the evil deeds of lawless men and Satan.

We read in Luke 22:3-4 (NLT) “Then Satan entered into Judas Iscariot, who was one of the twelve disciples, and he went to the leading priests and captains of the Temple guard to discuss the best way to betray Jesus to them.” Also in Acts 2:23 (NTL) “But God knew what would happen, and his prearranged plan was carried out when Jesus was betrayed. With the help of lawless Gentiles, you nailed him to the cross and killed him.”

This apparent paradox can easily be solved by the Molinistic model since God beforehand knew that those men would kill Jesus in those circumstances. This possible world was feasible to God, since it provides the path for salvation, and He therefore chose it from all other possible worlds.

Molinism also provides a solution on how prayer can influence God’s mind without Him “changing” it. There is a multitude of biblical passages that seem to indicate that God does not change His mind. For example “God is not a man, so he does not lie. He is not a human, so he does not change his mind.” (Numbers 23:19, NLT) and “I am the Lord, and I do not change” (Malachi 3:6, NLT).However we also see in the bible passages that seem to indicate that God in fact does change his mind. For example after Moses pleaded for God not to destroy the Israelites the bible says “So the Lord changed his mind about the terrible disaster he had threatened to bring on his people” (Exodus 32:14). Matt Slick writes about this paradox by saying that it is absolutely true that God knows all things and has ordained all things, but at the same time it is also absolutely true that God urges us to pray in order for Him to change things.[8]

From the Molinistic perspective it is easy to reconcile these two absolutes. Once a possible world is chosen and actuated by God, His mind in a linear timeline from the start to the end of that world does not change. However, by applying Middle knowledge, God would have been fully aware of what prayers would have been prayed in all possible worlds and would have taken them into account before choosing a possible world. The divine foreknowledge of these prayers is therefore the feedback mechanism by which human prayers can influence the mind of God before a possible world is decreed to exist.

In explanation of the biblical texts that seem to indicate the changing of God’s mind, for example Exodus 32:14, Craig responds by saying that God predestined not to destroy His people. The Hebrew author of Exodus only used literary devices to portray the narrative and interaction with God from a human perspective.[9]

There are also good philosophical grounds for the doctrine of Middle knowledge. As already mentioned, without Middle knowledge human freedom is completely annihilated.[10] Craig formulates his argument as follows:

- If there are true counterfactuals of creaturely freedom, then God knows these truths.

- There are true counterfactuals of creaturely freedom.

- If God knows true counterfactuals of creaturely freedom, God knows them either logically prior to the divine creative decree or only logically posterior to the divine creative decree.

- Counterfactuals of creaturely freedom cannot be known only logically posterior to the divine creation decree.

From premises 1 and 2, it follows logically that

- Therefore, God knows true counterfactuals or creaturely freedom.

From premises 3 and 5, it follows that

- Therefore, God knows true counterfactuals of creaturely freedom logically either logically prior to the divine decree or only logically posterior to the divine creative decree.

And from premises 4 and 6, it follows that

- Therefore, God knows true counterfactuals of creaturely freedom logically prior to the divine decree.[11]

Paul Helseth disagrees with Craig. He argues that all events by moral agents are completely determined by God in order for Him to control the outcome. According to him one should be careful to quickly dismiss the Augustinian-Calvinistic traditions since God is no respecter of persons.[12]If Helseth is correct in his assertion, then God is not only responsible for all good choices of humans, but also for all the sinful ones. This has not only major theological implications since it removes punishable guilt from humans, but it also attributes an evil and sinful nature to God.

Craig points out that universal and divine causal determinism cannot offer a coherent interpretation of scripture as it clearly nullifies human agency.[13]For example if God want humans to love Him but is forced to do so, then what is the point? Craig compares this with a man using a stick to move a stone as the world becomes a charade whose only real actor is God Himself. Reality is made into a farce.[14]

Others such as Gregory Boyd embrace open theism which advocates that complete free will can only be free if God neither determines nor even knows what they will be.[15] He describes this open model along the lines of a children’s “Choose your own adventure” book. The narrative in this book would unfold to a certain point where the reader gets to choose from several alternatives how the narrative would unfold. The narrative would continue along the lines of the choice made until a next point of choices is reached.[16] He argues that this combination of human free will and God acting in-between results in several possible endings.

Craig argues that a major problem that arises from this view is that it denies God’s divine omniscience. If God has only limited knowledge about humans would do in the future, it would be impossible for God to control the future. This is not only unscriptural, but it would result in strong theological problems. For example, Jesus predicted that Judas would betray him when they had supper for the last time. If God was unable to know this contingent future, He could be proven wrong if Judas decided not to go through with it. This would make God not only less powerful, but also a liar. This concept of libertarian freedom can be much better explained by the Molinistic model. The application of Middle knowledge alleviates the major conflicts listed above and shows that both determinism and free will can exist in harmony without violating any biblical, theological or philosophical truths.

Conclusion

In the minds of many theologians and Christians sovereign determinism and human freedom are complete incompatible ideas. To them it appears that if God determine all things, all human choices are preordained. On the other hand, if humans have complete freedom to choose, God does not seem so all powerful. Multiple models ranging from extreme Calvinistic views to extreme Arminian views attempt to provide a reasoned response about the interaction between God’s determinism and human choice. However, some of these models suffer from several biblical, theological as well as philosophical problems that render its conclusion powerless.

The Molinistic model seeks reconciliation between these extreme worldviews. Should God possess such Middle knowledge it provides Him with complete sovereignty while at the same time allowing human beings the complete freedom to make choices. This is not only in line with what scripture teaches about divine predestination but it also provides satisfactorily answers for theological challenges regarding prayer and paradoxes. This view furthermore maintains the fallen position of all humans and the need for salvation, which they can freely accept. The Molinistic view therefore reigns superior to other prominent views listed in this study when it comes to these rational and theological arguments.

It is important, however to note that even though Molinism has great explanatory power it cannot be proven beyond reasonable doubt. The importance however of this study is not to prove this view, but rather to illustrate that human free will and determinism are not mutually exclusive. It is clear that there is at least one very probable model that illustrates this. And since this notion is proclaimed by the Bible, this reasoning provides once again strong evidence of the truthfulness of scripture.

Furthermore Christian scholars need to admit with humility that the issue of God’s perfect will is a complex issue. The most gifted scholars might be able to write millions upon millions of books on this issue over ten thousands of years and still not come close to even start to grasp the comprehensiveness and complexity of the powerful and loving mind of God.

[1]Dennis Jowers, William Lane Craig, Ron Highfield, Gregory Boyd, and Paul K. Helseth, Four views on Divine Providence (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2011), Kindle Location 1584.

[2]Craig, Four views on Divine Providence, 1535

[3]Ibid., 1516

[4]Kenneth Keathley, Salvation and Sovereignty: A Molinist Approach (Nashville: B&H Publishing Group, 2010), 16.

[5]Craig, Four views on Divine Providence, 1558

[6]Ibid., 1582

[7]Ibid.

[8]Matt Slick, “Can we change God’s mind with prayer?,” http://carm.org/prayer-change-gods-mind (accessed May 12, 2013)

[9] William Lane Craig, “Can God Change? – Closer to Truth interviews William Lane Craig”, http://www.reasonablefaith.org/media/can-god-change-robert-lawrence-kuhn (accessed May 12, 2013)

[10]Craig, Four views on Divine Providence, 1778

[11]Ibid.

[12]Helseth, Four views on Divine Providence, 375

[13] Craig, Four views on Divine Providence, 4901

[14]Ibid.

[15] Boyd, Four views on Divine Providence, 3549

[16] Ibid., 4901

Craig, W. (2008). Reasonable Faith (Third ed.). Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books.

Craig, W. (n.d.). Can God Change? (R. Kuhn, Producer, & PBS) Retrieved May 12, 2013, from Reasonable Faith: http://www.reasonablefaith.org/media/can-god-change-robert-lawrence-kuhn

Craig, W., & Ludemann, G. (2000). Jesus’ Resurrection: Fact or Figment? (P. Copan, & R. Tacelli, Eds.) Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press.

Jowers, D., Craig, W., Highfield, R., Boyd, G., & Helseth, P. (2011). Four Views on Divine Providence. Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

Keathley, K. (2010). Salvation and Sovereignty: A Molinist Approach. Nashville: B&H Publishing Group.

Plantinga, A. (2001). God, Freedom and Evil. Grand Rapids: Harper & Row.

Slick, M. (n.d.). Can we change God’s mind with prayer? Retrieved May 12, 2013, from Christian Apologetics and Research Ministry: http://carm.org/prayer-change-gods-mind

Leave a Reply